They are the barrels traditionally used in Bordeaux, holding 225 litres. The word is also used loosely for those used in Burgundy and Beaujolais where both are properly named "pièce" which are virtually the same size as each other and as the barrique.

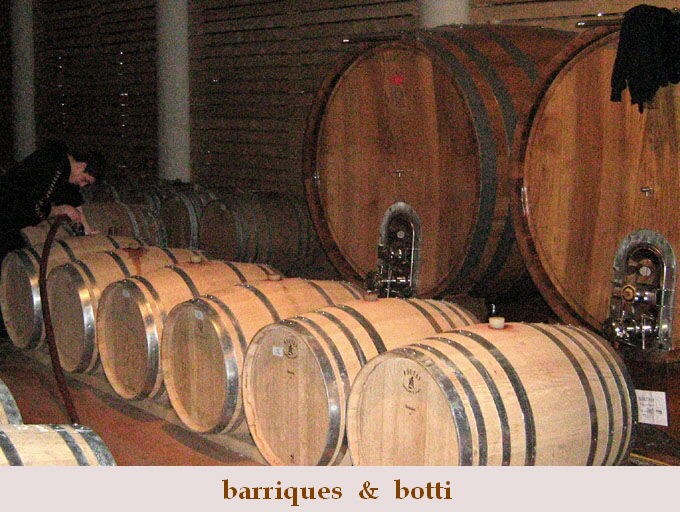

The point about them in the current context is that they are very much smaller than the barrels used in producing Barolo and Barbaresco; generally twenty times smaller. And while these bigger barrels are treated, and introduced carefully to fine wine maturing to ensure that no element of the wood gets into the wine, the barrique is often used new with the deliberate intention of adding wood substances to the wine. The smaller barrel presents a greater surface to a given quantity of wine so all effects take place more quickly. A barrique has three times the contact with the wine as a sixty hectolitre butt or "botte", two and a half times that in a 35 hl botte. It therefore also has more than twice the exposure to oxygen as that from the big butt, and it tends to get sloshed from barrel to barrel (racked, travasato) more frequently. And the bourgo/bordophile old guard insist on saying that wine from the 60 hl barrel is more likely to become oxidized! You also will read pseudo scientific asides implying benefits to the “development” of the wine. - but all the barrique sales-talk is about adding taste and smell. It is seriously claimed that fixing the colour is improved; but at what devastating price? And Aussie Merlot is still more decorative.

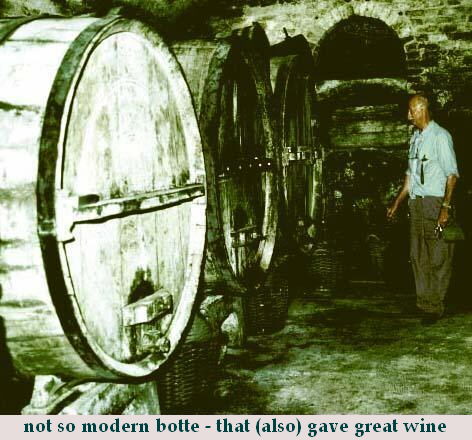

The traditional barrel in Piedmont is usually about 50 hl, but commonly between 25 and 60, and up to say 100. Slavonian oak is used in favour of Italian oak not because of chemical characteristic, or even a peculiar permeability to air; it is rather because of exceptional dimensional stability as it dries out, and again is filled with liquid. They don't leak. Then again there just isn't much Italian oak. Chestnut could legally be used, but I never met it being used in anger.

The wood for Bordeaux comes from Tronçais or Allier forests in the Auvergne. (The required characteristic of Allier oak was of course that it would make good ships to kill the British, not it's smell). By long tradition the characteristics have become part of the character of Bordeaux and of Burgundy wines and this deviation from "the product of the fermentation of grapes" too established to question for a moment. (However - the influence of oak on the bouquet or oral sensation of these wines was seldom mentioned until the 1980s; now every second tasting note has it. If any oak is "well integrated" no one can detect it!).

When high quality wines began to be produced in the "New World" they were made mainly from French varieties and to that extent were bound to be compared directly with wines from the same grapes in France - and wine makers followed traditions established in France. This all seems fair enough so far. But when wine importers and writers in USA and UK dared to extend beyond the familiar 'Claret and Burgundy' (and beyond similar wines arriving from Australia and Chile) to Italy they immediately preferred any that happened to taste and smell like good old Claret. And that meant of French oak above Italian grapes. In the 1970s this would often be second-string or the individual's experimental wine rather than a mutation of - say - Chianti or Barbaresco. Again, some Italian producers, notably in Tuscany, started - like the Aussies and Chileans - to make wine from French grape varieties in the French tradition. Many foreign critics went crazy over this Italian Claret; among all this demanding stuff with new perfumes and high acidity (compared to Bordeaux of course) was this very well made wine which was above all familiar. Or as they described it "good". Multitudes of professional wine writers who had for ever been condescendingly telling mere paying consumers not to confuse personal taste with quality were doing that to a man (of either sex).

(Among writers in the 1970s I must specifically exclude Hugh Johnson. He clearly and fairly preferred the best Bordeaux to the best Barolo - and the best Burgundy came a place higher still. But he wrote of great Barolo that was like Barolo, and that its merit lay in being just that. He also said of oak in 1971 "... it should not be obvious enough to be identified as oak " - and that was mainly about wines of which it was an acknowledged component).

Some influential Italian producers were not content to seize on the fact that critics were captivated by Italian oaky Cabernet Sauvignon, and use it to educate them. This was the time to say “Now you admit that we are capable of making fine wine - so give your respect and attention to what we make finest and best: Barolo”. But instead they capitulated to pressure from - mainly - conservative anglo-saxons who only like Barolo that smells like Bordeaux. So they increasingly allowed the smell and flavour of French oak to displace the delicate perfumes and savours from Barolo’s grape and terrain that were their greatest contribution to the world of fine wine. Then overseas critics started rating wines by giving them by points! There is a facile but trendy myth around, that most things can be measured. But quality, among diverse entities? No. I was slow in understanding how crass, nonsensical and misleading this is; it took me nearly five seconds. But then buyers started believing the scores. I won't insult sheep at this point. Then prices followed - particularly - in the rich successful dimwit sector of the market that dominates some economies, aided by the terrifying force of fashion.

The situation is now that if you go to buy the wine that has been known and loved for a century as Barolo, you know you risk buying a bottle that says it contains Barolo but simply does not. It will be legally Barolo of course - as if that were any excuse. The moment of opening the bottle is then utter disappointment; even (say) to a Bordeaux lover who would like something different today. Saying it is "better" is as nonsensical as it is insulting. It is different, so preferable to someone who happens to prefer that different wine. It's like someone who likes long haired dogs telling a bulldog lover that a long haired bulldog is "better". But you can look at the bulldog before you buy it! The typical wine consumer can never taste before buying, and very rarely read about the bottle they are about to buy - something that wine professionals seem to forget.

Perhaps the kernel of this entire thesis or diatribe reduces to "The label should tell you what's inside!"!

This is the only thing that DOC legislation can realistically attempt to do: guarantee that "Barbaresco" on the label means Barbaresco in the bottle. It fails at the only hurdle.

RIP 225 litres of Barbaresco...... an oak stave through its very heart ...

Oak flavour and smell can be given to wine by immersing oak chippings in it. This is done in Australia, so giving a posh pong to a plonk that is not properly posh. (It smells and tastes 'fine' without being 'fine'. You see?).

Just a word about the tonneau: The tonneau bordelais is equal to four barriques, 9hl. The one now commonly used is 5 hl. Use of fairly new tonneaux therefore may, confusingly, introduce an intermedate practice. And for differing reasons. For instance it is just a small barrel for the odd remaining 5hl.

And please notice how often writers opposed to the use of traditional Barolo barrels, preferring traditional Bordeaux barrels, refer to the former as big old dirty barrels. There is no reason at all to assume (or to misinform you) that a big old barrel is a dirty old barrel any more than that a big old man is usually a dirty old man.

© john wheaver 2006 (who?)

Home List of PRODUCERS {"V da U"} Selected (favourable) comments on "V da U" Italian and English